Cost and schedule overruns in infrastructure projects are still commonplace. According to global research by McKinsey & Co (2016), construction projects are typically overrun by 20 per cent on schedule and 80 per cent on cost.

The sector is addressing this challenge and there is a growing movement to improve the efficiency and productivity of construction projects. This issue is most problematic for state agencies entrusted with managing infrastructure assets. This is compounded with the additional challenge of managing the information and maintenance of the physical assets throughout the project life cycle.

There is no doubt that the construction industry has embraced information technology to improve efficiency and productivity of processes during planning, design, construction and operation of assets. New techniques such as lean construction and integrated project delivery are well developed and there is a genuine willingness to innovate. One such evolving innovation is Building Information Modelling (BIM), which is internationally recognised as a best-practice approach to successfully manage information throughout the asset life-cycle

BIM has gained significant traction within the Irish construction industry, and though National BIM Council Ireland’s primary aim has been to develop a “national roadmap to optimise the successful implementation of BIM Level 2 and beyond”, it is essential that this receives the investment, focus and time to ensure it is a success for everyone.

There is a reluctance to lead BIM implementation in projects and this responsibility is typically transferred to suppliers who are rapidly acquiring a BIM skillset and the ability to manage associated risks. If the Irish state is to develop a more strategic approach to BIM implementation, it needs to step up to the challenges and risks associated with BIM implementation.

Lessons learnt can and should be captured from the international landscape, building on the experiences of other countries’ approaches with a view to defining a framework for a national BIM implementation. Many organisations are still unaware of the potential benefits of BIM and hesitant to take risks that require the introduction of new ways of working. There are conflicting opinions in the industry, such as one that BIM is not necessary for a small country like Ireland; BIM is best managed by the private sector, the Irish construction industry is not ready for it, and so on.

The simple reality is that BIM has already been implemented successfully in some high-profile private projects in Ireland and is recognised as a competitive advantage in construction or engineering project environments.

It is imperative that Ireland’s state agencies which are delivering construction projects prepare their organisation to adopt BIM practices as a driver of efficiency, better financial gains and as best practice to maintain assets in the future. Most of the state agencies already produce CAD-based drawings, saved as hard copies, and thus lack proper information management and digitisation. This issue can be addressed though BIM.

There are ad hoc pockets of BIM expertise in Irish state agencies but what is lacking is a defined framework to harvest lessons learnt, standardise practices and develop a knowledge bank to share expertise.

International adoption of BIM

As BIM is relatively new to Ireland, it is essential to study and understand the progress and to analyse how successful BIM has been in other countries. This will help the state agencies to understand the benefits and risks and enable an effective implementation of BIM.

BIM is a buzz word in the world construction and engineering business these days. The construction industry is slowly embracing digital technology to improve its work processes and productivity. One of the main agents of this transformation is BIM. The EU Public Procurement Directive encourages the use of BIM in public works by public contracting authorities (Official Journal of the European Union, 2014). The consultation process is currently under way by the EU BIM Task group regarding BIM implementation programmes (McAuley, Hore and West, 2017).

The implementation of BIM in Finland, Denmark, Norway and Singapore has the significant support of the state agencies. These countries are medium to small size in terms of population and area. The policies of the governments in these countries are easier to implement nationwide than in big countries (Wong, Wong, Nadeem, 2009). In western European countries, 97 per cent of French and German and 49 per cent of UK BIM users report a positive perceived return on their overall investment in BIM (McGraw Hill Construction, 2014).

BIM in Ireland

The Irish state has not been immune to high financial losses in large infrastructure projects. Tobin (as cited in McAuley, Hore, West, 2012) points out that in 2004, there was a cost difference of 40 per cent between tender and scheme completion. Some of the large projects like Dublin Port Tunnel were significantly over budget. In an attempt to address this, the Irish government oversaw the introduction of the Capital Works Management Framework (CWMF) in 2007.

The aim of the CWMF is to ensure that there is an integrated methodology and a consistent approach to the planning, management and delivery of public capital works projects, with the objectives of greater cost certainty, better value for money and more efficient project delivery (McAuley, Hore, West, 2012). The objectives of CWMF can be achieved by the BIM process with the use of collaborative contracts.

The Government Contracts Committee for Construction (GCCC) (2017) in its discussion paper of ‘A Public Sector BIM Adoption Strategy’ proposes one of the actions as “Prepare a strategy for the adoption of Building Information Modelling across the public capital programme and to mandate the method to be adopted across the public sector”. Many commentators argue that the GCCC suite of contracts are not created in a way to promote collaboration. A collaborative approach with BIM is proven to be more effective for successful projects. This collaborative approach can be encouraged in the industry by redrafting the GCCC suite of contracts to include use of BIM processes and technologies (McAuley, Hore, West, 2012).

McAuley, Hore and West (2017) studied BIM practices across the globe in their research. They recommended that a structured BIM programme is needed for Ireland and provided the following enabler programmes for implementation of BIM, as lessons learned from their global BIM study:

They also highlighted that the success of these work packages will be dependent on leadership, expertise, experience and a successful programme of collaboration between government and industry.

Role of state agencies in BIM

Effective ways to improve construction projects are through increased participation and collaboration of all stakeholders. The role of state agencies is crucial as they drive change in the industry. They can bring better value for taxpayers’ money and encourage the market through procurement. Government policy and public procurement are considered powerful tools for driving the change towards BIM.

Different roles of state agencies

It is imperative that the government leads and encourages agencies and departments to formulate strategic plans and policies for the timely implementation of BIM for the benefit of the construction industry (Wong, Wong and Nadeem, 2011).

It can also provide leadership to orient the construction industry towards the digital age (EU BIM Task group, 2017). The adoption of BIM will ultimately be driven by state and semi-state agencies as the ultimate owners of construction projects (Porwal and Hewage, 2013).

The EU BIM Task group (2017) has identified state agencies can benefit from BIM in three stakeholder roles:

It is also equally important that the state agencies need to clearly understand the implementation mechanisms, determine the level of change required within their organisations and evaluate how best they can achieve this change (Abhabi and Alshawi, 2015). They are often hesitant to mandate BIM as they think that the market is not ready for it and are afraid to increase project costs by limiting competition (Porwal and Hewage, 2013).

Importance of BIM representative in state agencies

The literature emphasises the importance of a BIM representative from the state agencies’ side in construction projects. NIBS (2017) recommends that the state agencies should designate a BIM representative for larger and complex projects.

The BIM representative should be a person with a clear understanding of BIM and operations requirements of the organisation. They say that BIM representative should be able to perform the following duties:

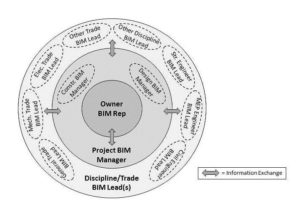

The role of the state agencies and the BIM representative is critical in BIM implementation. The various BIM roles is shown in the following Figure 2.

Figure 2: BIM role and responsibility chart. Source: National BIM Guide for Owners, NIBS (2017)

BIM implementation plan

The most successful organisations in implementing BIM are those who have developed a clear BIM strategy. CICRP (2013) developed a guide to owners for integrating BIM in their organisations. They say that the core principle of the BIM planning procedure should ‘Begin with the end in mind’. They propose a structured approach to effectively plan the integration of BIM within an organisation.

CICRP (2013) have proposed three core planning procedures. They are:

1) Strategic planning

2) Implementation planning

3) Procurement planning

At each planning process, six planning elements should be considered. They are as follows:

• Strategy – define BIM goals and objectives;

• BIM uses – identify methods in which BIM will be implemented. They could be for generating, processing, communicating, executing, and managing information;

• Process – documenting the current processes, designing new BIM processes and developing transition processes;

• Information – information needs of the organisation, including the model element breakdown, level of development, and facility data;

• Infrastructure – technology infrastructure to support BIM including computer software, hardware, networks and physical workspaces;

• Personnel – the roles, responsibilities, education and training of the active participants.

Strategic planning

CICRP (2013) strategic planning procedure provides guidance that a state agency can use to plan BIM at organisational level. Prior to the start of the strategic planning, it is important to build a planning committee. The success of the team lies in the perfect selection of individuals who have background, knowledge and experience with BIM and its processes.

When assembling the BIM planning committee, it is necessary to involve personnel with specific responsibilities and capabilities including (CICRP, 2013):

• BIM champion – an individual who is technically skilled in BIM and can champion the planning throughout the organisation;

• Executive representation – decision makers who have authority to grant access to resources, for example, time, funding, personnel and infrastructure;

• Middle management representation – motivated individuals who can contribute to the process and who are supportive of improving the process and manage the change. Individuals who will be able to monitor and manage the progress change;

• Technical workforce representation – individuals who might be directly affected by the adoption or change. Implementers of BIM process.

The main purpose of the strategic planning procedure is to determine the BIM goals and objectives and the roadmap on how to accomplish them. The three main steps involved in strategic planning are (CICRP, 2013):

• Assess

• Align

• Advance

The assessment should focus on both the internal analysis of the organisation and external analysis of the market. This should include some of the aspects such as business processes, organisational structure, culture, procurement strategies, financial considerations and market positions.

This should give an idea from the organisation perspective as to how far it’s ready for change and establish those aspects which require enhancement (CICRP, 2013).

Some of the items that can be included on the goals are reducing operational and lifecycle costs, improving operational workflows, understanding and defining information needs and so on.

Once the goals are established, identify the BIM uses for these goals. This process can highlight the BIM objectives and uses for the organisation (CICRP, 2013).

At this stage, road mapping processes can be used to plan, visualise and implement the strategy. It helps to bring a structured approach to the implementation of BIM. This part is crucial as this might differ among organisations as the goals and objectives of each organisation can vary (CICRP, 2013).

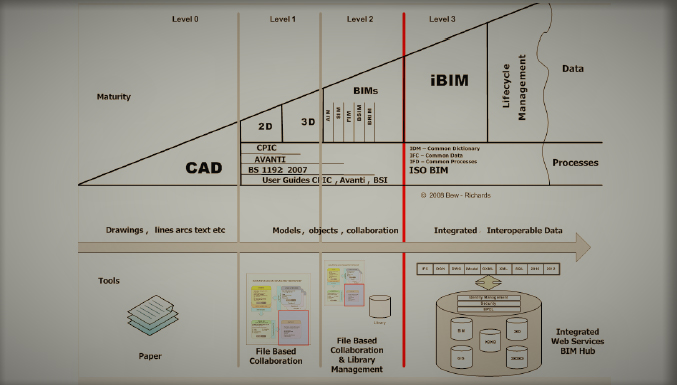

BIM Industry working Group (2011) has developed a BIM maturity level model as shown in Figure 3. This gives guidance for the state agency and the supply chain to understand the processes, techniques and tools at each level of maturity.

It has supporting guidance and standards on how they can be applied to the projects and contracts in the industry. This can be used as a guidance by the state agencies to identify where they are in the maturity level and where they want to progress.

Figure 3: BIM Maturity levels. Source: A report for Government Construction Client group, BIM Industry working group (2011)

Implementation planning

After the strategic plan, the implementation plan can be developed (CICRP, 2013). At the implementation stage, organisational and people-centred issues pose the greatest challenge for BIM (Porwal & Hewage, 2013). The implementation plan should consider the following items (CICRP, 2013),

1.) Process

2.) Information

3.) Technology and Infrastructure

4.) Education and Training

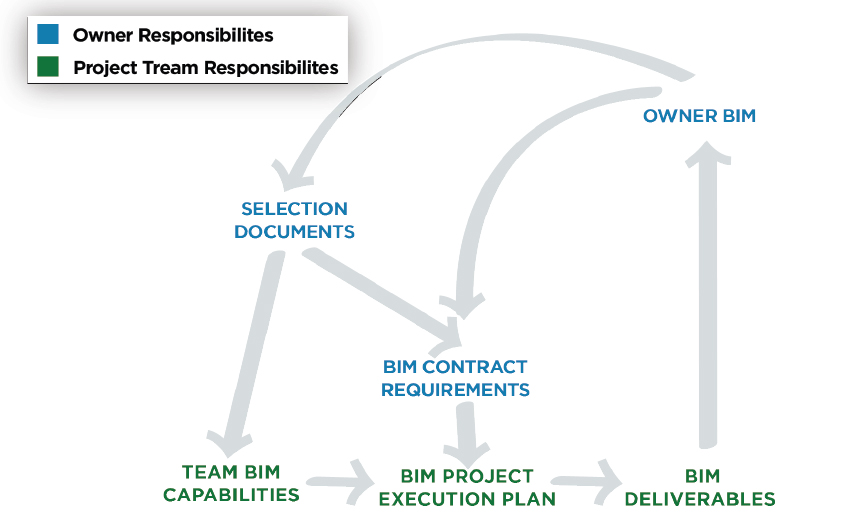

Procurement planning

It is important that a construction client should develop a procurement strategy prior to any project involving BIM. These contract requirements are required to see if the client’s BIM needs are met. Also, this supports the BIM implementation throughout the lifecycle of the facility, (CICRP, 2013).

The core procurement components are:

• Team selection

• Contract requirements

• BIM project execution plan

Selecting the proper team and setting the contract requirements should be fundamental to the BIM use within a project. The project execution plan serves as a tool to align project BIM uses to the owner’s needs, as mentioned in the contract. Figure 4 shows the schematic representation of requirements of BIM procurement planning.

Figure 4: BIM Procurement planning.

Source: BIM Planning Guide for Facility Owners, CICRP (2013)

Team selection

The state agency shall request qualifications and experience from the potential team members. They can use appropriate tools to score them. This tool can be named as a ‘request for information (RFQ)’ tool. Secondly, they can also request price and description of the BIM uses to be performed. This document or tool can be called a ‘request for proposal’ (CICRP, 2013).

Contract requirements

The BIM contract is aimed to document the BIM requirements of the state agency. It focuses on the goals and objectives of the organisation. The project team then develops a project execution plan which will contain much of the project specific BIM requirements, processes, and information workflows (CICRP, 2013).

BIM project execution plan

The client can develop the standard BIM project execution plan prior to the first BIM project. This serves as a foundation, which will contain information needs and requirements of the client. The BIM champion or manager plays a key role in supporting development and revision of the BIM project execution plan. This document can contain details on inter-operability and data transfer requirements of clients. At this stage, the state agency can specify to own the BIM model to use it throughout the facility life cycle. This helps to protect the intellectual property and liability limits by the contractor who creates the model (CICRP, 2013).

Summary

There is no single approach to BIM that will suit all the construction clients (Saxon, 2016). Adoption and application will vary depending on the requirements of the organisation and the project environment. Nonetheless, there is a real need to develop a more strategic and standardised approach to BIM implementation. The adoption of BIM is still in the infancy in state agencies in most countries. Success lies in both cultural and technological change and a more proactive approach. Digital transformation is impacting all industry sectors and standing still is not an option. State agencies play a critical role in information management and knowledge management in large projects and physical infrastructure. The indirect benefits of BIM maturity include improvement of document management, information management and knowledge management. It is time for the government to lead the way on BIM and develop national BIM guidelines. This can be developed by following UK BIM standards and customising them to suit the Irish construction industry. Nationwide BIM education and training programmes need to be launched with a vision to mandate BIM on all future public projects. BIM has the potential to enhance benefits realisation for the state, contractor, and the paying public. Let us at least try and lay the foundation stone and define a level 1 BIM national framework that is within the reach of all interested stakeholders.

Authors: Jansi George, Transport Infrastructure Ireland; John McGrath, course director, MSc Project Management DIT

References

1) Aubin, P (2012). Revit Architecture 2012. Clifton Park, N.Y.: Delmar.

2) Azhar, S (2011). Building Information Modelling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 11(3), pp.241-252.

3) BIM Industry Working Group. (2011). A report for the Government Construction Client Group. Building Information Modelling (BIM) Working Party Strategy Paper. Communications. Retrieved August 2017 from http://www.bimtaskgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/BIS-BIM-strategy-Report.pdf

4) EU BIM Task Group (2017). Handbook for the introduction of Building Information modelling by the European Public Sector. Retrieved July 2017 from http://www.eubim.eu/handbook/

5) Imagining construction’s digital future. (2016). McKinsey & Company. Retrieved July 2017, from http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/imagining-constructions-digital-future

6) Wong, A., Wong, F. and Nadeem, A. (2010). Government roles in implementing building information modelling systems. Construction Innovation, 11(1), pp.61-76.

7) NBS (2016). What is BIM?. Retrieved August 2017 from https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/what-is-building-information-modelling-bim

8) NIBS (2017). National BIM Guide for Owners, National Institute of Building sciences, Washington DC. Retrieved July 2017 https://www.nibs.org/page/nbgo_formm